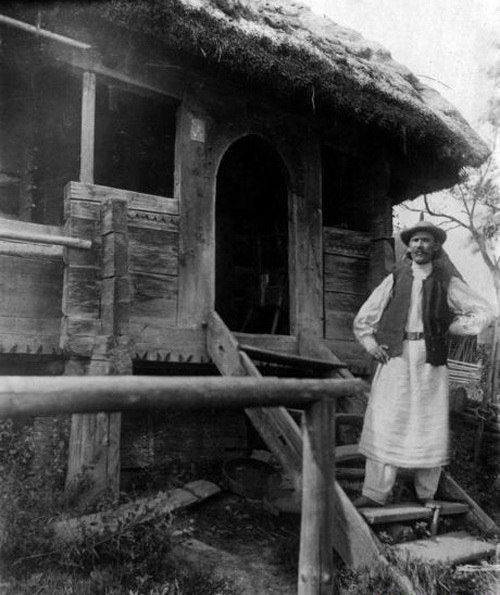

Dear friends, we decided to take a closer look at the homes of Ukrainians living in the end of 19-th and beginning of 20-th century tell you more about them.

What did my grandfather’s native house look like? What was the layout of the interior of the room he was born in? Where was that house located and what was it built of? Were there any conveniences? What did people sleep on and where did they cook their food? What did they use to light and decorate their homes? Did they have any domestic animals? We will try to give answers to these and many other questions in our future publications about housing. I also invite you to take a Ukraine tour with Dorosh Heritage Tours to learn even more and have authentic experience in the country of your ancestors.

So, before trying to describe a house built by your ancestors, I would like first to help you understand how exactly they were choosing a place for construction, because this was one of the most important decisions in the life of a new family.

In our investigation of this issue, we have found out that it was not all that simple! Let’s delve into this in more detail.

Ukrainian practicality and mysticism

It appears that choosing a place for a house was a three-step process in all regions of Ukraine. The first step was purely practical. Indeed, practicality has always been one of essential elements of the Ukrainian mentality. Every true householder had to consider such factors as proximity to water (river, stream, sufficient level of underground waters), sources of building materials (woods, stones, clay), terrain features (protection from winds, floods), fertility of soil, previous buildings on that site, distance to the church and to shynok (inn), the price of the plot, etc.

However, it’s very interesting that along with the householder’s practicality and purely rational experience, the choice of a place for building a house was influenced by another typical element of your forefather’s mentality which is mysticism that developed due the closeness to the soil, and dependence on nature. The ancestors of the Ukrainians have always divinized the forces of wild nature. They found sacred all the things that were associated with it and that lived in it, be it dryads (“mavky”), wood spirits (“lisovyky”), vampires (“upyri”), wolfhounds (“vovkulaky”), demonic children (“poterchata”), and other nice mystical creatures that played a huge role in their daily lives.

I know, you’ll find it hard to believe but until now Ukrainians remain pagans deep in their hearts. Though being Christians, we still observe pagan holidays or celebrate Christian holidays in a pagan way (we will focus on it in more detail in our future stories). Yes, the Ukrainians use smartphones, tablets and the Internet, but even nowadays many of us try to protect our children from an evil eye, do not pass things over the threshold, believe in a spells, magic and potions. Let alone your forefather who lived, say, 150 years ago.

Follow the advice of the elders

Let’s get back to your ancestral house. As a second step in choosing a location, your ancestors referred to folk wisdom, beliefs and interviewed senior fellow villagers to collect information about the applicability of a chosen place for building a house.

The way it happened and how mysticism influenced the selection of a location for housing may be seen in the example of a famous ethnic group, the Boiko, namely their representatives living in the western part of Galician Boikivshchyna – present day Starosambirsky and Turkivsky districts of Lviv region of Ukraine. Be ready for a cultural shock because many residents of these villages still believe in it.

The locals believed that there are so-called “evil places” where “something prevents from building” (Grozyova village in Stary Sambir district).

Which places were believed to be foul, according to your grandfather? First of all, an “evil” place could be identified by certain signs and characteristics:

- A house was never built on a burned area (Kryvka village in Turkivsky district),

- at the place where there used to be a church, burial, where someone killed somebody, or where somebody hanged himself etc. (Grozyova village in Starosambirsky district)

As in the other regions of Ukraine, the “evilest” places were believed to be a border, a path, a road or a crossroad:

- “if a house is built on a path or on a border, there will be no luck in keeping the house, the cattle will not grow well (Babyno village, Starosambirsky district);

- “one should not even repose on a border or path in a field” (Mygovo village)

What were the explanations of such taboos? The reasons were very simple and clear:

- “one shall not build a house on a path or a border because these are the places where the devil sits” (Topilnytsya village in Stary Sambir district),

- “one shall never block a path because an evil force walks there” (Ripyana village in Starosambirsky district),

- The residents of Topilnytsya village are saying that one man once dressed a wood on a border, and when warned about the devil, he answered jokingly “So what! I will dress it on his head”, and then he immediately injured his leg.

Certain beliefs were associated with a respectful and sometimes timid attitude to nature, and only in a few cases did these beliefs have any practical explanation.

People avoided building houses on former plum tree gardens “because plum trees have thorns and houses build on that place bring no luck to the people” (Stara Ropa village). However, sometimes (Volia Kobylianska village) prohibition to erect houses on plum tree roots has more rational motivation which is avoiding mold.

The houses were not to be build where elder trees grew (Turya, Babyno, Grozyova, Tchapli, Gubychi, Syshytsya Rykova, Stara Ropa villages in Stary Sambir district; Boberka in Turka district). Motivation for such prohibition was as follows: “in elder sits a devil (“hodovanets“) who was killed by thunder and who now frightens people (Sushytsya Rykova village). In Turya village there usually was a strict taboo on cutting an elder because “..those who cut elder die…”

People avoided places where periwinkle spread out “because where periwinkle grows there a dead man lies”(Tchapli village).

In Tchapli peolpe had warnings concerning seed plots as well. An interviewed man from that village told that his grandfather had once built a house on a seed plot despite being warned by a local craftsman (Shayda) who said that if he built a house there his wife would live for only seven years. The grandfather was married three times and each of his wives died in seven years…

Consult the fortunetellers

If no restrictions to building a house were identified, your grandfather proceeded with a third step of choosing a place and performed a final “compliance” test using a system of fortunetelling. A grandfather visited a fortuneteller (“vorozhylnyk“) (Terlom Rosokhy, Velyka Sushytsya, Strashevychi, Myhovo, Vovcha Nyzhnya villages in Stary Sambir district; Yablunka Verkhnya, Boberka, Shandrovets of Turka district, etc.).

Vorozhylnyk could tell whether a place was “clean” sitting at his home and without visiting a site (Myhovo, Terlo, Boberka): “he opened a Psalter from which he could see the future…”

However, it happened (Grozyova village) that after a layout was made, the vorozhylnyk visited the place, put down some special small loafs at the angles of a future house and stayed there until morning, “observing something”. In the morning he could tell a householder whether the place was suitable for building and whether any angle needed to be moved.

Sometimes fortune telling was done by a householder himself. For example, in Turya village, in the evening before starting the building works the craftsman put dill (“okropets, krip“) and some other herbs on a chosen place tied in a knot and pressing it with a rock. In the morning he viewed the site and could tell whether the place was good. In Velyka Linyna village a craftsman came to the place, “burned a newspaper at four angles and observed something”. In Drozdovychi village people used to put an egg in the center of the site (“plyats”) for the night (sprinkling it with some soil). If an egg was wet in the morning, in meant that the house should not be built there.

People in Bobertsi, Turka district, used bread for fortune telling. Before starting the works, stones were put at each of the four angles and bread (quarter of a loaf) was put at the top of each stone in the evening. In the morning people checked whether the bread was still there. This procedure was repeated three nights in a row: “if nothing takes the bread away for three days, it means that home will be followed by a good luck and building can be started. If something takes the bread away, this is a bad sign and one should look for some fortuneteller who can advise how to redesign the house…”

As you can see, even the choice of a place for construction was quite a complex ritual action from a modern point of view. A kind of a stunning blend of practicality and beliefs. However, our great-grandfather would likely consider modern life too simple.

It is interesting that many of these beliefs still exist, being deeply rooted in the souls of conservative Ukrainians and effectively coexisting with the modern reality ….

Revealing and exploring these peculiarities is an extremely exciting thing and if you are interested in learning more about this, I suggest that you take your Ukraine Heritage Tour with us. We also invite you to follow Andriy Dorosh, Ukraine tour guide and genealogy researcher on FB to get notifications of our new posts. We will be happy to share our observations and discoveries.

Sources:

Oleksandr Strazhyi, “Ukrainian mentality: Illusions. Myths Reality.”

Fedir Vovk. “Ukrainian ethnographical and anthropological studies.”

Roman Radovych. “Customs and rites associated with the construction of housing in the west of the Galician Boykivshchyna”