We are used to seeing the word “Obstetrix” in all birth records we research. What kind of reality hides behind this term?

As we often do, I invite you to travel back in time with Dorosh Heritage Tours and have a tour of Ukraine (Austro-Hungary and Poland at that time) to learn more about my GG-grandmother’s occupation, and the part that this work played in early Ukraine. I am happy to guide you and share our discoveries.

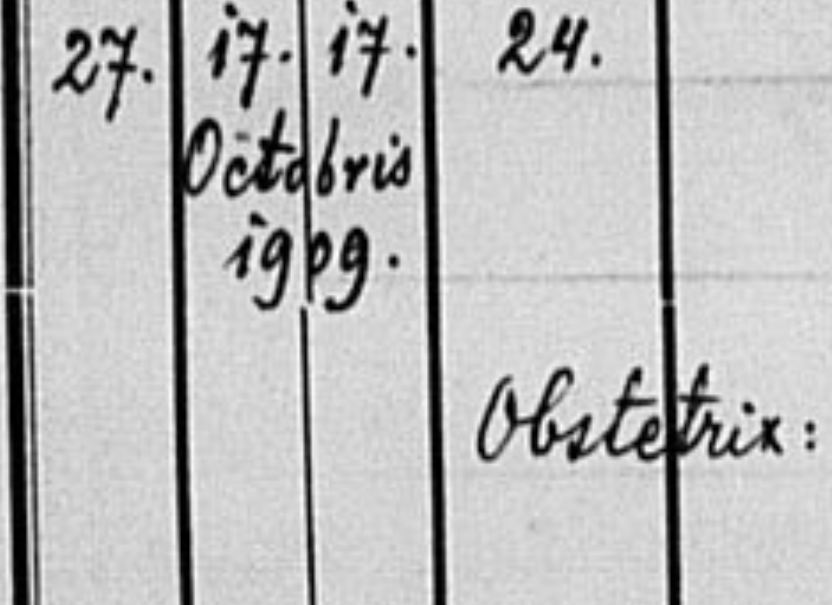

When researching my roots I discovered that my great-great-grandmother, Agafia Bogachevska, who lived in the town of Zheldec, Galicia, was an “Obstetrix”, so it was especially interesting to research this topic.

“Obstetrix” means a midwife, and there were 3 categories for midwives in Galicia in the 2nd half of 19th – early 20th century: certified, those who did not have a diploma but were trained by certified midwives, and those who were were self-taught. All of them played an important role in the health delivery system, particularly in the absence of qualified doctors and proper care facilities.

The diploma of a midwife could be obtained in special schools in Krakow or Lviv, and the diploma allowed the midwife to assist at childbirths, independent of doctors. Public health services in Austro-Hungary were the responsibility of the Ministry of the Interior, which administered all health personnel, including certified midwives. At the turn of century, there were annual conferences of certified midwives held, at which their registers and delivery instruments were checked. The Ministry of the Interior published a book titled “Service Rules for Midwives” in 1897. It contained sections on the midwives’ general responsibilities, pregnancy, delivery, infant and child care and midwives’ legal obligations. All certified midwives had to own this book. At the District level, the activity of midwives was regulated by The Medical Officer of Health, who inspected them during his regular tours.

However, certified midwives operated mostly in cities and bigger towns (e.g, there were 16 midwives in Chortkiv, 18 in Borshchiv, 31 in Terebovlia and 19 in Zalishchyky in 1900), so the people of the villages had to rely mostly on self-taught midwives. Depending on the location, they were referred to by different names: “baba”, “baba-povytukha”, “baba that ties the umbilicus”, “needful baba” and others. Let’s call them baba in this post. I really doubt that my GG-grandmother from Zheldets was a certified midwife. So let us learn more about self-taught babas.

A typical baba would be “50-60 years old”, someone who had raised their children and grandchildren, and now can go to help people”. A good reputation and stable lifestyle were crucial features of a good baba, since it was believed that the baby delivered with the help of a “dirty” baba would grow ill and have a scrofula (a bacterial disease of the cervical lymph nodes) or inherit her negative features. People believed that experienced babas could foresee the future of the baby: “Baba would go to the window and then say who, when and why the baby will die”. There were usually several babas in the village, but it was not good to change the baba one used for childbirth: an offended baba could cast a bad spell on the baby, by making it cry all the time or causing other misfortune.

Being a baba was considered a kind of vocation and before the baba started her practice, she asked the priest for a special blessing, ordered a special prayer service or a Great Acaphistus service to St. Mary, who was considered the patron of the pregnant.

When the time of the childbirth came, either the husband or the closest relative went to call the baba. They tried to keep it a secret and do it in the evening if possible: the fewer people who knew about the moment of childbirth, the easier it would be. It was the worst sin for the baba to deny the request to help; she just did not have any right to refuse, if she was asked. However, according to the tradition she had to be asked several times, and she would always say no to the first invitation. The explanation goes that this way the childbirth would go without any complications.

The baba came to the house with bread, blessed water and different medicinal herbs. She would always pray and bow to the icons before taking care of the birthing mother. Every experienced baba had her own conjuration that she pronounced over the water that was given to the future mother to drink. It was also put on the forehead, the breast and the belly, and the rest was dumped over the threshold. After the baby was born, the baba prayed, made a sign of the cross over the baby, and sprinkled it with blessed water.

It was believed that a difficult delivery was the divine scourge. In this case, the baba was the first to implore forgiveness. Then, the wife and the husband asked each other for pardon. In the most difficult case, they asked the neighbors for pardon, as well. The birthing mother had to pray and drink the water that was used to wash the icon. Some of the family was sent to ask the priest to open the holy gates in the church: it was believed that it is the closest way for the baby to come from heaven. In Galicia there was a tradition to “open” everything: windows, doors, take the hair out of braids, take off the rings and earrings, untie all the knots on clothes, etc., (Voroniaky village of Zolohiv county, Lviv Oblast). This tradition has been preserved to the present time.

The baba tried to help by giving different herbal teas (rye, nettles, calamus and other), bathing the birthing mother in an infusion of buckwheat straw, giving her a bottle to blow into, rubbing her belly with butter, etc. Those who were not “professional” used some different methods, such as hitting the belly, making the birthing mother take buckets with water out from the well, or jump down from the table, etc.

However, in fatal cases, the baba was never accused and she was always invited to assist in a delivery again.

Cutting the navel cord was the other important task of the baba. There was a tradition to cut it on the item that would have to do with the future occupation of the baby. A girl had it often cut on the comb (a special comb for wool). A boy had it cut on the axe. The parents who wanted their children to be literate, asked the baba to cut it on a book. The baba used “konopli” – hemp thread – to tie the navel.

The first bath of the baby was another important mission of the baba. She knew what kind of herbs should be used to make the girl beautiful, and to make many boys love her. Of course, a book and money was put under the bathing tub to make the child educated and rich (Voroniaky village of Zolohiv county, Lviv Oblast).

To be allowed to perform the delivery of another baby, the baba had to have “zlyvky” done. It meant that she made her spirit clean by pouring water onto her hands in a special way.

The baba was often asked to take care of the new mother after birth, and help her about the house to cook, clean and wash.

The parents tried to thank the baba in the best possible way. It was common to present linen for a dress and to give her bread. It was a must to invite her for the baptism, and the baba had to bring a special dish, baba’s “kasha” (cereal). The godparents would put money onto a plate for the baba. In the village of Strashevychi of Stary Sambir district, Lviv oblast, the money was thrown onto the floor and the baba had to sweep it and share it with the new mother.

In many villages of Ukraine, a baba was present at childbirth, along with a professional obstetrician, till as late as the 1950’s. It was believed that her presence diminished the labor pains.

Dear friends, if you like our articles, please follow Andriy Dorosh, a genealogy researcher and tour guide in Ukraine on FB, to receive notifications of our next posts.

Literature:

Iryna Kolodiuk. Baba and Her Function in the Folk Medicine of Polissia in 19 – Late 20th Century

Lesia Kostiuk. Birthday Rite in Galicia in the Secod Half of 19th – Early 20th century.

Roman Huzij, Lesia Horoshko. Birthday Rites and Traditions in Stary Sambir District

Stella Hryniuk. A Peasant Society in Transition