– I am going to Canada, I said to my wife.

– Where is that, Canada?

– Thank God, she does not know! I thought.

– It is close. Just about 6 hours by train from here. I lit a cigarette, since I did not have enough courage to look into my wife’s eyes.

This is an actual dialogue that took place before Pylyp Jasnovskyi, a Ukrainian emigrant, started his journey to Canada from Dubliany near Lviv, Galicia, on Mar 31, 1911. Pylyp walked to Lviv on foot, and traveled the rest of the way to Bremen by railway. He took a train to Oswiecim, and from Oswiecim to Bremen to board the ship heading to Port St. John, New Brunswick, Canada.

How did my ancestor ever manage to get to the coast to take the ship? It is a question that I hear often during our heritage tours of Ukraine and Poland. The journey by railway that was the most common way of getting to the European ports from Bukovina and Galicia. Let us explore what it was like. I invite you travel in time with Dorosh Heritage Tours of Ukraine to see how it happened: we are going back to the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

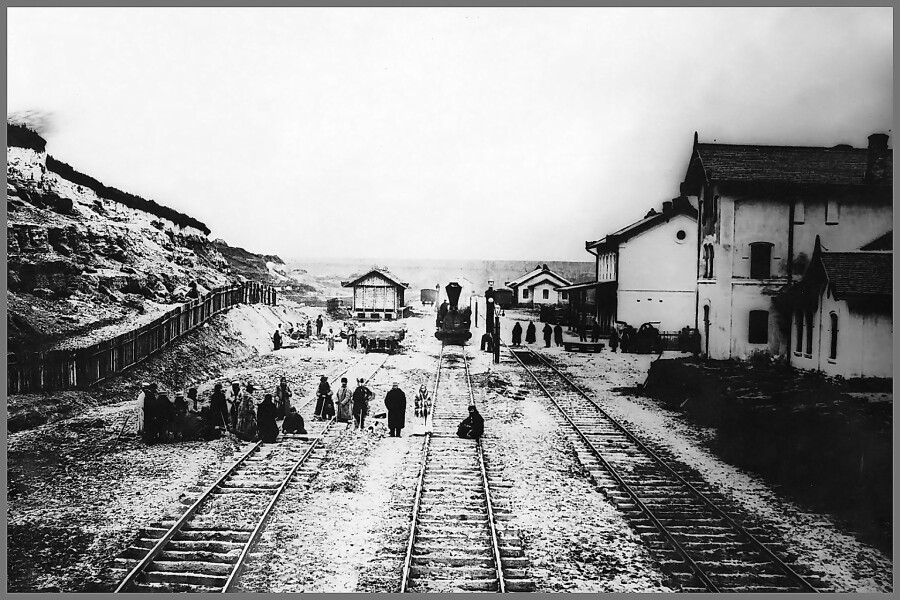

At that time, the majority of emigrants traveled via Lemberg (Lviv) and Przemysl to Oswiecim, a small town near the border of Austro-Hungary and the German Empire. If you know which town your family comes from, you can trace their way to Oswiecim on the map of the Imperial Railway System of Austro-Hungary dated 1900.

Yes, it is the same Oswiecim (Auschwitz in German) that is known for the concentration camp of WWII. Before WWI, it was a big transit hub for emigrants traveling by train to German ports from present Ukraine, Poland, Russia, and Belarus. The chances that your ancestor was there are quite high. Oswiecim was a typical Galician town with a population of about 10,000 citizens, predominantly Jewish. It had a market square with a town hall, shops, hotel “Hertz” (named after the owner of Hamburg Emigration Agency – HAPAG), the ruins of a castle, several churches, a synagogue and about 10 Jewish prayer houses. However, it was not a safe place for emigrants. The economy of the town was doing well due to its special location: it had a railway station near the border. Emigrants contributed to a large part of its economy. The town was literally flooded with numerous groups traveling to do seasonal work in Germany, and with emigrants heading overseas. Ukrainian, Polish and Slovak peasants, servants, shepherds, Galician and Russian Jews, small craftsmen and merchants, runaways, criminals and swindlers all came to look for cheap accommodation and taverns.

There were offices of two German transatlantic shipping companies in Oswiecim: HAPAG and North German Lloyd. They competed and they used all possible illegal means to lure to the town as many emigrants as possible. Oswiecim was full of prowlers, who earned their living by exploiting emigrants. Fraud and even violence were common (more in our future posts), and railroad workers, as well as police, customs officers and border guard units often appeared to be integral parts of the mafia.

Despite the fact there was a shorter route to Germany through the town of Zywiec, train conductors convinced emigrants to buy the ticket that would take them to Oswiecim, making them easy prey for the local emigration agents. The police at the train station arrested those who refused, and documents and money were confiscated. The chief of guard explained that going by the shorter route is against the law, and those who did not believe this were put into cells as punishment. Even regular passengers who were not emigrants often became the victims of this fraud.

Once the train arrived at the Oswiecim train station, the workers of both emigration agencies bombarded the emigrants. The best method was to take them to an office, wrest their luggage from them, and run. This way the emigrant had to follow for sure.

If some emigrants already arrived with ship tickets that had been bought by their families in the US or Canada, the head of the customs department at the train station, Marceli Iwanicki, came into the game. Fully prepared, he went to meet the trains with the emigrants, and took those who were not willing to buy tickets at HAPAG agency to his office. Here he would put the pressure on the helpless emigrant, as Iwanicki was paid 1 gulden for every passenger who he forced to buy a “proper” ship ticket.

Oswiecim railway station was located in the village of Brzezinka (Birkinau in German), just 3km (1.6 mile) from Oswiecim. Yes, another sadly remembered concentration camp of WWII: Auschwitz-II (Auschwitz-Birkinau). Emigrants changed trains in Brzezinka, and crossed the border at Myslovitz/Myslowice to proceed to Bremen or Hamburg. If your ancestors sailed out from any of these ports, you can try to trace their way to the port on the map of the railway system of the German Empire.

German emigration regulations were strict. The state was worried that emigrants would stay in German cities, or bring in cholera and typhus. In 1886 all emigrants had to have in their possession 800 deutschemarks per adult and 400 for each child. Otherwise, Prussian customs officers would not allow them into the country. To avoid inspections at the crossing point, emigrants used the services of smugglers. The smugglers took them by secret trails and put them on trains about 2-3 stations away from the border. The emigrants were instructed not to buy direct tickets to Hamburg or Bremen at any small stations close to the border. Instead they were to travel to some bigger towns along the way and buy the tickets there. Smugglers from Podgorze have a very bad reputation. Podgorze is a small town near Krakow, where many emigrants left the train to avoid inspections at the large train station of Krakow. The smugglers charged 10 guldens (more about Austro-Hungarian money here) per person, and they packed 8-10 people into a horse cart. They then took them to the area near Biezanov, a neighboring town, and would leave the emigrants somewhere in a field at night. Of course, the emigrants were told that they were in Germany already. Ten guldens was a lot of money at that time, since it cost about 60 guldens (about 100 deutschemarks) to travel from Hamburg to New York. Many of those emigrants were detained by the police and sent home. Those who got to Germany never complained; they were afraid to be arrested for crossing the border illegally.

As you can see, the train journey was not smooth at all, and I am sure it was very stressful and the emigrants had much to fear. I do not think that every emigrant got into this sort of trouble on their way to the coast, but the chances were very high.

Use this link if you like to sign up for my post updates. We do have many more interesting stories to tell.

Literature:

Pylyp Yasnovskyi. Under the Native and Foreign Sky

Martin Pollack. The Emperor of America: The Big Escape from Galicia