This little sketch will be interesting to those whose family originates from Eastern Galicia and who would like to feel the real atmosphere of their ancestral village. We invite you to travel in time with Dorosh Heritage Tours of Ukraine.

We will use the help of modern historians, as well as Ivan Franko (1856-1916), the famous Ukrainian writer, scientist, public and political activist to take you to Nagujevychi village in Boryslav District, Lviv Oblast of Ukraine (please, check its location on the map) in the late 19th-early 20th century. So here we go, let’s learn more about the real life of our ancestors!

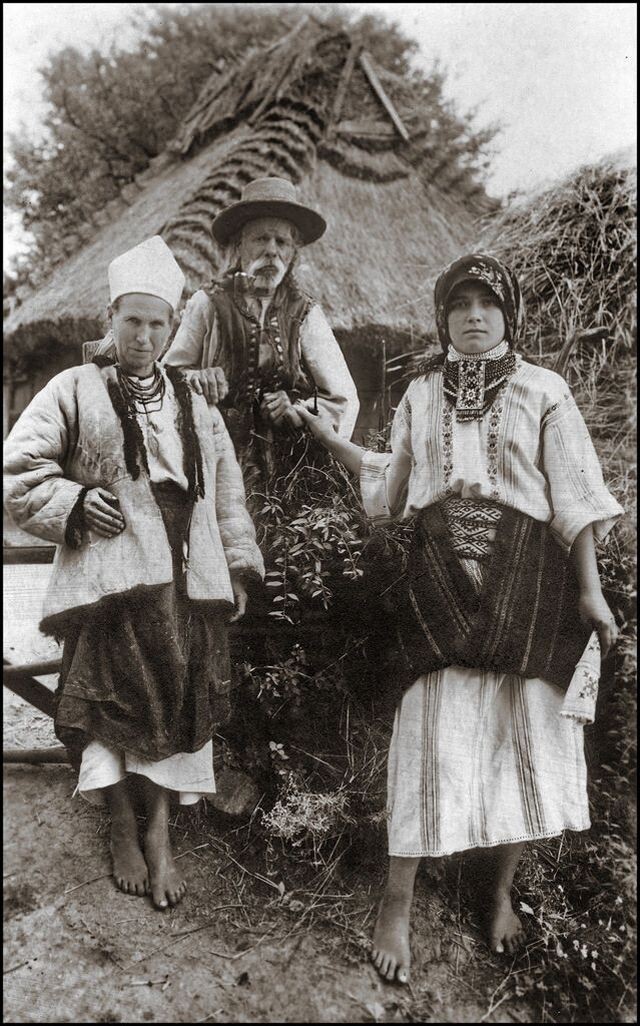

Nagujevychi (Nagujowice) was a predominantly Ruthenian village. Except for a couple of Polish landlords, it was mostly settled by small Ruthenian farmers who owned a few, very thin strips of land scattered all over the village, and kept a cow, a goat and a few pigs in the barn. They often had only one pair of boots and one sheepskin coat for the whole family. To save boots they walked barefoot until the first autumn frost. Oat scones, boiled cereals, potatoes, cabbage and red beets were the common food. Meat was eaten on Christmas and Easter only, and sometimes at weddings or funerals. Thus, it was really easy to keep fasts imposed by priests: 40 days before Easter and Christmas, two weeks before St. Peter and Paul’s and Dormition of the Mother of God, also on Wednesdays and Fridays all year long. If you were a real pietist you could easily fast on Mondays as well! Horilka (vodka) was one of the main eats too, and a big boozing session at least once per week was the point of honor even for the poorest.

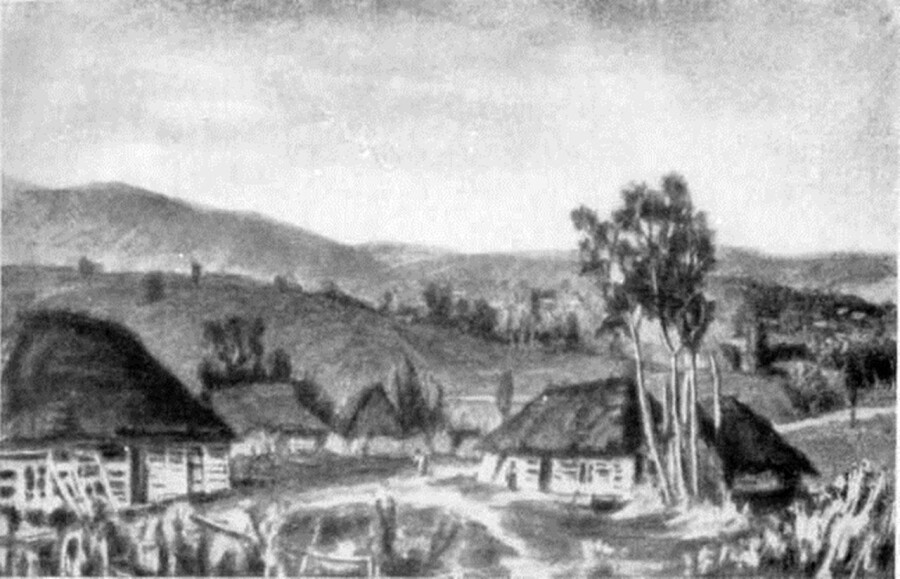

Let us have a look at the description of “an average Galician village” by Ivan Franko who was born in Nagujevychi. We believe that he imagined his native village when writing this piece of narrative.

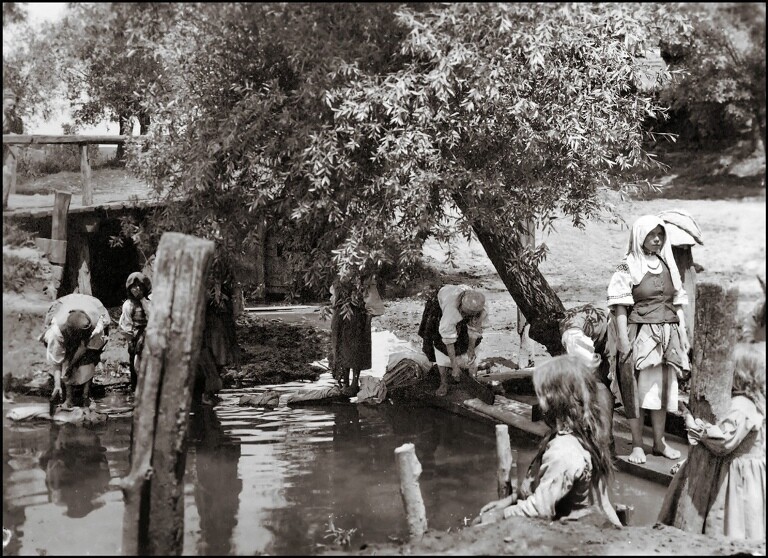

“… an average Galician village … is located by a river or a pond and you can see a great many old fruit trees and willows from a distance. There is a church in the center. Surrounded by green fields, the village has a quite picturesque and idyllic aspect. However, when you come closer you can see that the small idyllic huts scattered here and there, appear to be growing out of the ground, and are actually quite dirty, covered with rotten straw and often falling apart.

Small windows of about a half of a square meter are never opened, and there’s hardly any light let in. There’s usually only one room inside. It performs the function of a kitchen, a dining room and a bedroom. It is where the calves, piglets, lambs, chicken, geese stay, and where the potatoes are stored in winter. It is hard to believe that they all can fit in this cramped room. There is very little space indeed: as a rule, the room is not bigger than 15-20 square meters. It is never higher than 2.5 meter. Low ceilings are common since it conserves heat, thus saving you from spending a lot on heating.

A big primitive masonry oven made of clay occupies more than one fourth of the room. It is used for baking bread, but it also performs the function of a hospital, a warehouse, children’s room and a drier (read more about masonry oven here). Old people need warmth. They do not have any separate beds so they sleep there in winter along with children and other family members. Women often sleep inside the oven sticking their heads out when the fire is off. The bed is the privilege of the house owner and his wife. They always sleep together with the whole family being witnesses. Older boys go to sleep in the barn in both winter and summer. All of those who do not sleep in the bed use clothes as sheets and an armful of straw is their pillow. Even the host who sleeps on a bed cannot be considered a man of pleasure. This bed is rather a euphemism: just a couple of boards covered with straw and a piece of homemade linen. The same kind of linen, substituted by a coat in winter, serves as a blanket. Mattresses are very rare, and they can be found in the houses of the richer farmer only.”

How big was the village? According to church records in 1890 there were 1647 citizens (including “Upper”, “Lower” Nagujevychi and suburbs). Fifty Nagujevychi citizens were Polish, 76 were Jewish and the rest were Ruthenian in 1902.

On average, there were about 10 babies born in each family at the beginning of the 20th century. However, many of them died as there was no doctor there at all. Only 8 children of 18 survived in the family of Ivan Sarabrin, and 5 children of 15 in the family of Fedir Twardowski. Diseases such as smallpox, typhus, scarlet fever, pneumonia were very common: about 56,000 people died in Galicia every year. Cholera came to Nagujevychi in 1873 and took 160 citizens. In 1875-1882 a cholera epidemic resulted in the loss of thousands of lives. A future post will cover this epidemic in more detail.

There were 2 wooden churches in the village (in “Upper” and “Lower” Nagujevychi), both named after St. Nicolas. He was one of the most admired saints in Galicia. Both churches belonged to the same parish and had the same priest who received the state salary of 108 guldens yearly before 1878 and 111 guldens after 1878. One of the priests, Michael Jednakij, owned 2 oil derricks and was quite well off.

There was a school in the village too. It was opened in 1818 and the teacher earned 250 guldens yearly which was a lot of money at that time (read more about salaries and expenses in this post). Accommodation in the school building, wood to heat the house and servants were provided free. It was the so called “trivial” (elementary) school located in a regular village house close to the church in Upper Nagujevychi. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was already a 7-year school based in 2 buildings in the village center. Boys and girls studied together, but they were registered in different school reports. In 1900-1914, many pupils were not allowed to move on to the next grade for such reasons as “deaf”, “dumb”, “stupid”, “cripple”, and had to repeat the earlier year with much younger pupils.

A Prosvita (enlightenment) department that aimed to preserve and develop Ukrainian culture was started in 1906. By 1907 there were 182 books in the local library, and 130 members were engaged in educational and cultural activity. They organized a drama club and a choir, with performances taking place in nearby villages as well. The authorities at this time were mostly Polish and did not support the Prosvita department’s efforts. As a result, there were always 2 or 3 boys on the lookout to warn about the gendarme coming to check what kind of play was being performed. As soon as he arrived, they started singing Polish songs or performing a piece of a play in Polish, a common occurrence in the times of the 2nd Polish republic. The gendarme was happy and left with a smile on his face.

In 1881 there were 9000 land plots owned by Nagujevychi citizens, only 150 of them were classified as the “soil of the 1st class”. The biggest landowner had 20 morgs (about 10 hectares or ha). Most citizens owned about 2-3 ha and many owned just a house (“khalupnyk”) or rented accommodation (“komirnyk”). The chances that your ancestor was “khalupnyk” or “komirnyk” are quite high and we will tell you about this phenomenon in one of our next posts.

A blacksmith and a builder were the most respected professions. There were also tailors, shoemakers and a cooper in the village. Many of the Jewish residents in the village were not peasants: Abba Bril owned the village tavern; Jacob Berger was the richest of Nagujevychi Jews as he owned a shop and a sawmill; Moshko owned a grocery store, and bought oats in autumn to sell at a very high markup in spring; he also bought calves to sell as meat at the markets of bigger towns, such as Drohobych and Boryslav. Some of the Jewish families were not any different from the rest of Nagujevychi population, and it was common to be friends, visit each other on holidays, and harness the horses together to cultivate land.

However, being either poor or very poor, the peasants were at the mercy of several masters: the landlord, the pub holder, the priest and the gendarme.

Peasants pastured their cattle in the forests and they paid a tax until an 1875 regulation, when Baron Monsfeld, the Minister of Agriculture, forbade forest pasturing, and the peasants were forced to use the roadsides to pasture their animals. About one-third of the cows that were the base of the family economy had to be sold since people now did not have any pastures. Of course, the prices went down: a horse cost about 50-80 krauzers on the market in 1877-78. As well, the fine of 5 guldens and 3-4 days of prison were levied for collecting brush wood in the forest. People were taken to the District Court in Drohobych town for cutting a tree, and the punishment was usually about 14-21 days in prison. The forest was one of the means of survival for the poorest: it was the source of wood, mushrooms, berries. “Forest cases” resulted in 42% of Nagujevychi citizens being sentenced in 1875-1882.

1883 was a very difficult year in Nagujevychi as winter lasted for more than 7 months. The most difficult years of the 19th century in Galicia were 1847, 1849, 1855, 1865, 1876 and 1889.

Poverty, cold, hunger, diseases, lack of employment, usury, and alcoholism made Ruthenian peasants easy prey for emigration agents who filled Galician villages looking for working hands that would be ready to bring the new lands of North America and Brazil into cultivation. Dreaming about the land flowing with milk and honey, the peasants flocked to the local administrative units to obtain international passports. There was a rumor, started by creative emigration agents after the mysterious death of Crown Prince Rudolf and his lover in Mayerling incident, that the Prince actually did not die, but moved overseas to distant Brazil to found a wonderful empire that he would like to settle with his beloved Ruthenians. He’s waiting for them with open arms to reward them for their loyalty. It caused a real “emigration fever”. There were other rumors, no less ridiculous, about a Russian Tsar and an Austrian Emperor making a deal to exchange their population: the Russian Jewish population would go to settle in Austria whilst Franz Joseph would send Ruthenians to Russia. Whole villages would pull up stakes, and police and the gendarmerie were used to stop peasants from crossing the border.

Dear friends, I do hope that this little sketch about village life will add to the general picture and understanding of our ancestry. We also invite you to tour Ukraine with Dorosh Heritage Tours to learn more about your roots. We will be happy to guide you! Also, follow Andriy Dorosh on FB so that you will not miss our next posts.

Note: We used random pictures of different Galician villages in this article, it is impossible to find good pictures of Nagujevychi.

Literature:

Ivan Franko. Galician Peasant.

Matin Pollack. Nach Galizien

Hanna Grom. Nagujevychi